What the latest scientific research reveals about talent development in sport

Most coaches don’t intentionally chase short-term success at the expense of long-term excellence. Yet many development systems quietly reward exactly that: early results, early selection, early specialisation.

A major review published in Science in December 2025 by Arne Güllich and colleagues questions whether this approach truly produces the world’s best athletes. Drawing on data from over 34,000 elite performers — including Olympic champions, international athletes, chess grandmasters, and Nobel laureates — the findings have direct implications for how we coach, select, and develop young athletes.

Early success and elite adulthood rarely align

One of the most consistent findings across sports is also the most confronting:

The athletes who perform best at young ages are usually not the ones who reach the highest level as adults.

Across multiple sports:

Roughly 82% of international junior athletes never reach senior international level

Around 72% of adult international athletes were never international-level juniors

Only about 10–15% of athletes overlap between junior and senior elite status

This means early selection identifies some future elites — but it misses most of them.

From a coaching perspective, this matters because many development decisions — selection, deselection, funding, training load — are made during years when performance is least predictive of long-term outcomes.

Many future world-class athletes were not outstanding early

Even among athletes who all reach elite levels, a surprising pattern emerges.

Athletes who go on to become truly world-class often:

Performed below many of their peers in youth

Progressed more slowly early in their careers

Surpassed early standouts only later, closer to peak performance age

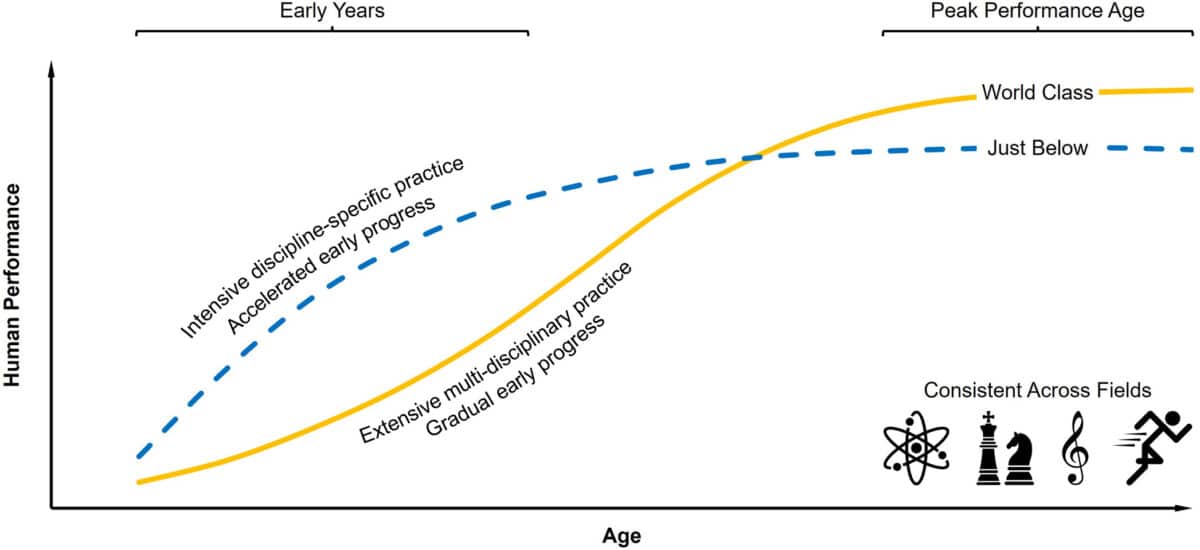

The development of the highest levels of human achievement (Güllich, et al., 2025, Science)

This pattern is not limited to sport. It appears in chess, music, and science as well. Peak performance is often negatively correlated with early performance among elite adults.

For coaches, this reframes how we interpret “average” or “late” developers. Slower early progress is not a warning sign — it may be part of a more sustainable trajectory.

What predicts youth success is not what predicts world-class performance

The review makes a crucial distinction often blurred in coaching discussions: the factors that predict early success differ from those that predict world-class adult performance.

Among youth and sub-elite athletes, higher early performance is associated with:

Early specialisation

High volumes of sport-specific practice

Rapid early improvement

Among adult world-class athletes, the pattern reverses:

Later specialisation

Participation in multiple sports over more years

Gradual early improvement

World-class athletes typically engaged in around two additional sports during childhood and adolescence. This was not casual play — it was structured, sustained involvement over many years.

Why broader development works better long-term

The authors propose three mechanisms that align closely with coaching experience.

1. Better matching

Trying multiple sports increases the chance an athlete eventually commits to the discipline that best fits their physical traits, learning style, and motivation.

2. Stronger learning capacity

Multisport athletes tend to develop:

Greater adaptability

Transferable movement skills

Better self-awareness as learners

These qualities support long-term improvement, not just early performance.

3. Lower risk of burnout and injury

Early overspecialisation increases the risk of:

Overuse injuries

Mental fatigue

Loss of motivation

Reducing these risks helps athletes stay engaged long enough to reach their peak.

What this means for coaches in practice

This research is not an argument against commitment, quality training, or high standards.

It is an argument against assuming that rapid early progress equates to high long-term potential.

Put simply:

Early performance tells us who is ahead now — not who is capable of becoming the best later.

From a Mozaiq-style performance perspective, this research supports a shift: from trying to identify “talent” early, to designing environments that allow potential to emerge over time.

Coaching principles supported by the evidence

For coaches working in youth and development pathways:

Delay irreversible selection and deselection where possible

Encourage participation in at least one or two other sports over multiple years

Value consistency, learning ability, and adaptability — not just current dominance

Interpret slower early progress as information, not failure

Measure development across longer time horizons, not single seasons

Programs that optimise only for early success risk producing exactly what they measure: early success — and little more.

A different definition of development success

The strongest message from the Science review is not that early success is meaningless — but that it provides incomplete information.

The athletes most likely to reach the highest level are often:

Still learning when others are winning

Still developing when others plateau

Still motivated when others drop out